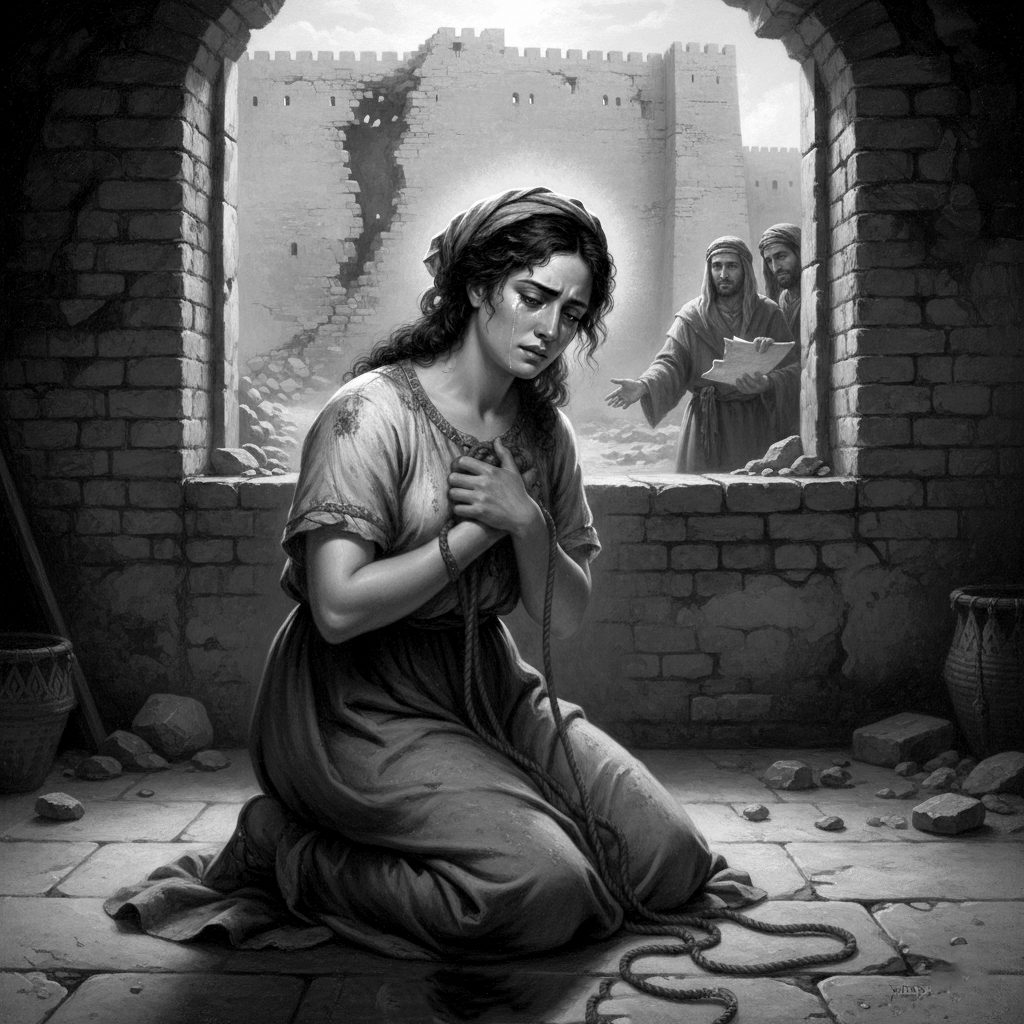

The story of Rahab stands as one of the most striking narratives of mercy and redemption in the Old Testament, demonstrating how God’s grace can reach even the most unlikely of individuals. A Canaanite prostitute, Rahab’s inclusion in the redemptive story of Israel subverts expectations about divine favor and covenant participation. Through her faith and obedience, Rahab not only experiences personal salvation but also becomes a crucial link in the genealogy of Jesus Christ. Her transformation from a marginalized outsider to a vessel of divine purpose reveals the character of God, who extends mercy to the repentant one, and incorporates the redeemed into His redemptive plan.

Rahab’s story occurs at a pivotal moment in Israel’s history– the threshold of the conquest of Canaan. God’s promise to give Israel the land of Canaan (Genesis 12:7; Exodus 3:8) was about to be fulfilled. The city of Jericho, a heavily fortified and strategically significant location, represented the first obstacle in the Israelites’ path.

Rahab’s social and moral status is identified as disreputable. In the ancient Near Eastern world, prostitution was often associated with pagan worship or economic desperation. By all cultural and moral standards, Rahab was an unlikely candidate for divine favor. Yet, in her encounter with the Israelite spies, Rahab demonstrates a theological insight and faith that far surpasses that of many Israelites.

God’s mercy is not confined by human categories of worthiness. Throughout Scripture, God often chooses the marginalized, the outsider, and the sinner to accomplish His redemptive purposes (Genesis 12:1–3; 1 Samuel 16:7; Luke 15:1–7). Rahab’s inclusion in Israel’s story serves as a profound statement about the nature of divine mercy.

Rahab’s confession of faith in recognizing the God of Israel

In Joshua 2:8–11, Rahab makes a theologically profound confession. It reveals both intellectual acknowledgment and personal faith. She recognizes Yahweh’s sovereignty and acknowledges His covenant promises to Israel. It is remarkable that Rahab, a pagan Canaanite, expresses faith in the God of Israel even before witnessing any of His acts personally. Her faith arises from hearing about God’s mighty deeds — the parting of the Red Sea and the defeat of Sihon and Og (Joshua 2:10). The writer of Hebrews commends her faith (11:31)

Her confession illustrates that true faith is not limited by ethnicity, gender, or past sin. Rahab’s acknowledgment of God’s supremacy reflects a spiritual awakening – an act of repentance and surrender that aligns her with God’s purposes. In this, she experiences divine mercy.

Mercy Displayed as God’s Compassion Toward the Unlikely

Mercy, in biblical theology, is the undeserved compassion of God shown to those who cannot save themselves. In Rahab’s story, mercy is seen in two dimensions: divine mercy extended to Rahab and human mercy extended through Rahab. Rahab’s occupation and background placed her under divine judgment, as the Canaanite nations were marked for destruction because of their idolatry and moral corruption (Deuteronomy 9:4–5; Leviticus 18:24–25). Yet God, in His mercy, allowed a window of salvation for someone who demonstrated faith.

The red cord Rahab used to mark her house (Joshua 2:18) becomes a powerful symbol of divine mercy. It parallels the blood of the Passover lamb in Exodus 12:13, a sign that protected the Israelites from death. In both cases, a visible token of faith marked those who trusted in God’s promise of deliverance. The scarlet cord thus prefigures the atoning blood of Christ, through which sinners receive mercy and redemption (Ephesians 1:7; 1 Peter 1:18–19).

Rahab’s act of hiding the spies was itself an act of mercy. She risked her life to protect God’s servants, choosing loyalty to Yahweh over allegiance to her own city. James 2:25 highlights this as evidence of living faith. Her mercy toward the spies was the outward expression of her inner transformation. Faith in God produced compassionate action. Thus, mercy becomes both the means and the fruit of redemption. Rahab received mercy and extended it to others.

The Covenant of Salvation

Rahab’s story progresses from confession to covenant. In Joshua 2:12–14, she appeals to the spies for kindness in return for her kindness to them. The Hebrew word used here, chesed, is deeply theological, often denoting steadfast love or covenantal loyalty. The spies took the oath to preserve Rahab and her household when Jericho falls. This covenant of protection reflects the pattern of God’s covenantal dealings with humanity. Rahab’s blessing flows from her alignment with the covenant people of God. When Jericho is destroyed, Rahab and her family are spared (Joshua 6:25).

Her deliverance is both physical and spiritual. Physically, she is rescued from destruction. Spiritually, she is brought into the covenant community of Israel. This foreshadows the inclusion of Gentiles in the New Covenant, where faith, not ancestry, determines membership in God’s family (Romans 3:29–30; Galatians 3:28–29).

Redemption in Rahab’s Story

Redemption, in biblical theology, involves deliverance through the payment of a price or the exercise of divine power. It is both liberation from bondage and restoration to fellowship with God. Rahab’s redemption can be understood in three dimensions: personal, communal, and messianic.

Rahab’s personal redemption begins with her faith and culminates in her deliverance from destruction. Once she was defined by her sin, now, she becomes defined by her faith. God’s redemptive power transforms her identity from Rahab the prostitute to Rahab, the faithful. Her story demonstrates that redemption is not limited by one’s past.

The most profound aspect of Rahab’s redemption lies in her place within the genealogy of Jesus Christ (Matthew 1:5). Through Rahab came Boaz, who married Ruth (another Gentile woman of faith), and through them came King David, and ultimately Jesus, the Messiah (Matthew 1:1–16). This genealogical inclusion demonstrates the continuity of God’s redemptive purpose: from Rahab’s act of faith emerges the lineage through which ultimate redemption — in Christ — enters the world.

The inclusion of women in the genealogy of Jesus, particularly Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathsheba, is remarkable in a patriarchal context where lineages were typically traced through men. Their presence highlights God’s sovereign grace working through unexpected people and circumstances. Each woman’s story includes social marginalization, suffering, or moral complexity, yet God used them to advance His redemptive plan. Their inclusion foreshadows the gospel’s message that God welcomes the outsider, restores the broken, and values the overlooked.

Theological Reflections

Rahab’s story reveals that God’s mercy transcends boundaries of race, gender, and moral history. The God of Israel is not a tribal deity but the Lord of heaven and earth (Joshua 2:11). His mercy reaches even to the condemned city of Jericho. Her example serves as a theological corrective to exclusivist notions of salvation, affirming the inclusivity of God’s redemptive plan.

Redemption is not merely a change of circumstance but a transformation of identity. Once despised and morally broken, she becomes a mother in Israel and an ancestor of the Messiah. This transformation reflects the essence of biblical redemption: God takes what is defiled and makes it holy, what is broken and makes it whole. Rahab’s life illustrates that redemption is both deliverance from sin and restoration into covenant relationship.

Rahab’s Legacy

The story of Rahab is a timeless testimony to the mercy and redemption of God. Emerging from the ruins of Jericho, Rahab’s faith shines as a beacon of hope for all who believe. Her journey from sin to salvation illustrates the heart of the gospel: that God, in His mercy, redeems the undeserving and incorporates them into His covenant family.

Rahab’s legacy extends far beyond the walls of Jericho. Rahab’s narrative serves as a paradigm for the mission of the Church. Just as she welcomed the messengers of God and found salvation, so also, the believers are called to welcome the message of the gospel and extend it to others. Her home became a place of refuge and salvation; likewise, the Church is called to be a place where sinners find mercy and redemption in Christ.

The story of Rahab offers powerful encouragement to women in India who face social, cultural, or economic barriers, many of whom live under the weight of stigma, silence, and fear. Rahab lived in a context where her identity and past placed her on the margins of society, yet she displayed remarkable courage, wisdom, and faith. Her willingness to take bold decisions, even in the face of danger, shows that women have the capacity to influence their families and communities, despite restrictive circumstances.

For Indian women trapped in cycles of exploitation, violence, or abandonment, and struggle against gender discrimination, limited education, or social stigma, Rahab’s story proclaims that their identity is not defined by their trauma. God acknowledges their pain, honors their resilience, and offers the possibility of renewal. Rahab’s transformation affirms that healing, safety, and hope are within reach. Her life encourages women to seek support, embrace their worth, and believe that restoration is possible. For Indian women, this affirms that their voices, skills, and leadership are significant, even in cultures that may silence them. Courageous choices can open pathways to healing, empowerment, and a hopeful future, even in the midst of adversity.

Rahab’s story invites everyone to recognize that the same God who showed mercy to a Canaanite prostitute continues to extend mercy and redemption to all who believe. Through Rahab, the scarlet cord of grace runs from Jericho to Calvary — a vivid reminder that God’s mercy triumphs over judgment, and His redemption reaches even to the farthest and most forgotten corners of the human story.